- Home

- Gwen Adshead

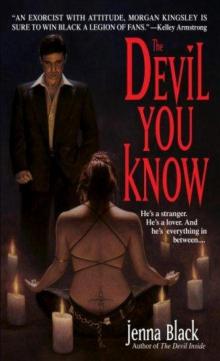

The Devil You Know Page 5

The Devil You Know Read online

Page 5

Tony described to me how he would leave a bar with a man to have sex in an alley or park nearby. He said he never gave them his real name, so when he punched them hard in the face after orgasm, he could run away confident that he could not be reported. Later, he stopped running off and instead took his victims’ wallets, threatening to find them and kill them if they went to the police. He lost count of the number of times he did this before the first murder. He had begun to hear talk around the bars of a ‘Thursday guy’ who was reported to be a sadist, a little out of control, so he decided to change his usual haunts and go to a different part of the city. That’s when he met his first murder victim.

It was his face that Tony saw in the nightmares. He was a lovely boy, he said, ‘with the bluest eyes’. He choked up at this and stopped talking. It was not easy to think about, he admitted. I felt nervous about what he might tell me. It is one thing to read about a killing on paper, and quite another to hear about it directly from the killer. As Tony began, he switched to the historic present tense, which confused me at first. I subsequently realised this was common in Spanish, which had been his first language. Later in my career, in my work with trauma survivors and through further study of the nature of traumatic memory, I would find that it was typical for many people (not only violent offenders) to slip into the present tense when describing painful events. The psychological explorer in me finds this fascinating: such a distortion to temporal reality is a way of unconsciously signalling how live their memories are for them, that they are not filed away somewhere in the past, where they belong. I always try and remember these kinds of verbal shifts to reconstruct later, noting down key phrases that stick in the mind.

‘We go to his house, and all the way there in the taxi I’m thinking, “I’m going to do it, I’m going to have him.” I know I can kill this one. He’s so young and trusting, and he has such a lovely face, peach fuzz, soft skin. His place is a flat at the top of a building, so we have to climb up two flights of stairs, stumbling and racing each other to get up there so we can fuck. We drink a bit when we get up there and take poppers, then we start to kiss, and I feel this urge to choke him that starts in my groin. He smiles up at me, those eyes of his – and he’s trying to look so sexy, and I can’t bear that look, those eyes, and that’s when I grab him round the throat. He isn’t strong. I’m stronger, much stronger, and soon … it’s done. I look at him and feel disgust. I hit him in the face, then kick him a few times, till I realise he’s not moving. He’s dead. Then I think I need to get out of there, but I’m afraid someone will find his body and I’ll get done. What can I do? Get rid of him, hide him – but how? Throw him in the river or a canal? It’s the middle of the night and I don’t even know where we are, what part of town. I think of dragging his body down all those stairs, but that’ll wake the neighbours for sure. I look around and decide I have to get him into a bag or a suitcase or something, and I ransack the place, find a duffel bag, but even though he’s small he won’t fit, and what if his body gets stiff? Outside the dawn is coming. I have to hurry. I can see the house backs onto some woods …’

He broke off. I knew what he was coming to, and it would not be easy to say in any language or any tense. Tony had decapitated his first victim, sawing his head off with a kitchen knife. The body and head were eventually found near each other, dumped in the woods. There had been much lurid public speculation about the profile of the monstrous mind that had done such a thing and what it all meant, but I was about to discover that the rationale had been quite prosaic. Tony kept his eyes fixed on the floor as he told me that he quickly worked out that the head was the heaviest part of the body, ‘like a bowling ball’, and so ‘I have to cut it off.’ ‘It’s hard,’ he said, and then, under his breath, ‘takes ages’. I waited as he gathered himself, his breathing shallow.

‘Once the job’s done,’ he resumed, ‘it can go in one bag, while the rest of him fits into another bag, and then I lug them both down the stairs, trying not to make a load of noise, to bump into anything or drop him.’ Only then did he look up at me to check my response, and I remember that I managed to keep my face still, just nodding thoughtfully – not as difficult as it might seem, because I understood that, for Tony, this was a practical part of ‘the job’. Learning to control emotional reactions to what patients say is a basic part of any doctor’s training, Medicine 101. Freud likened the work of therapy to surgery, and we wouldn’t think much of a surgeon who opened up someone’s abdomen and blanched or even ran from the room, crying, ‘There’s cancer everywhere in there!’ This is why we have therapy ourselves while we are training, to become aware of things that might get under our psychological skin. Again, we take our feelings about patients, whether negative or positive, out of the room to discuss them with our supervisors. During the session itself, it’s my duty to focus on my patients’ emotional experiences, not my own.

It did occur to me that the social banality of this particular session with Tony was absurd. Here were two people in a room talking about decapitation, but to anyone passing by and glancing through the glass panel in the door, there would have been no sign that we were having such a bizarre conversation. We might have been chatting about the weather. I saw no point in asking Tony more about the decapitation, a pragmatic solution to a difficult problem. I was mindful too of serial killer Dennis Nilsen’s petulant observation that people were more interested in what he had done to men’s bodies after death (dismembering them and flushing them away) than the fact that he had killed them. I asked Tony to tell me, when he was ready, what had happened after he disposed of the young man’s body. I was deliberately using the past tense, but he persisted with the historic present, in this vein: ‘Next day I go to work, and it seems to me like a dream. I convince myself it isn’t real, you know? And when he’s found, and it gets reported on the news, I just pretend to myself it isn’t me.’

In Julius Caesar, Brutus describes that same feeling: ‘Between the acting of a dreadful thing / And the first motion, all the interim is / like a phantasma or a hideous dream.’ Shakespeare’s eloquent summary is psychologically perfect, and also anticipates modern research which has shown how perpetrators of violence enter into a dream-like or ‘dissociated’ state during their offence. This makes the detail difficult to recall afterwards, and it becomes easier to think, ‘It wasn’t me,’ or ‘It didn’t happen.’

Tony went on, offering a further revelation, still in the present tense: ‘Everyone is talking about it in the Thursday bar where I go now. I do too – I even volunteer to walk one kid home so he gets there safely, and I feel good about that. But then I think I could do it again anytime, and nobody will know it’s me. I’ll do it, and it won’t matter because it’s not real.’ I nodded, thinking how this kind of denial was such a familiar human impulse, arising from a desire to preserve an image of ourselves as good people. I’ve heard divorce lawyers say that many clients, during their first meeting, will describe how their marriage broke down because their soon-to-be ex is a villain, while they are blameless. The lawyers nod and make a note, but they know such claims are only the start of the story, and the same could be said in therapy. Denial for Tony ran deep and allowed him to keep an awareness of his bad self out of his consciousness; if his violence were real, it would matter, and that would be unbearable. The fact that he had gone so far as to convince himself that he was protecting a potential victim from harm was pretty remarkable.

Tony went on to tell me about the two other men he had picked up in different bars and killed, disposing of their bodies as best he could. He did not decapitate them, which meant it took some time for the police to connect the first murder to the later ones. Eventually, they caught him after finding a matchbook from his place of work in the last victim’s flat. After his initial denials, Tony confessed and pleaded guilty to all three murders. He got three life sentences, with a twenty-year minimum ‘tariff’ – the length of time before he could apply for parole. Today, that would be seen as too lenient,

and he would likely get life without any chance of parole.

Not all therapy sessions are made up of big reveals like this. Most days they are unremarkable. We sit, we talk, we listen, two human beings exploring thoughts together. Tony and I didn’t return to the murders again, but we did talk more about his nightmares, which were still ongoing. In one of our sessions, he complained bitterly to me that the patient in the room next door had gone and talked to the staff about him shouting in the night, which had upset him. He’d confronted the man, accusing him of lying. A row ensued, until his nurse Jamie stepped in and revealed that the other patient was right, it was Tony who was doing the shouting in the night. Tony couldn’t believe how unreal this felt. But he also didn’t think Jamie would lie. He told me he ‘couldn’t get his head round it’, but he didn’t argue about it any further. I thought the fact that Tony was able to tolerate his nurse saying something that he found uncomfortable might be an indication that he was finding the therapy helpful. I believed Jamie had sensed this and done the right thing, and I told Tony that I benefited from my own discussions with the nurse. I had the impression that Tony liked to know that Jamie and I were connected, almost like a parental couple who were keeping him in mind.

That interchange between Tony and Jamie provided an opportunity to look at Tony’s perceptions when distressed. The mind can switch off when there is too much to take in, I explained to him, and we can all ascribe things that we don’t like about ourselves to other people. Building on this idea, I asked him whether he could make out what the man next door said when he cried out in the night. Could he hear any words? ‘He’s shouting for help. Over and over again.’ It would have been too much for me to have said it to him at this point, but it occurred to me that the man shouting for help might have been a memory fragment of a dying man’s last desperate screams. So I asked if it was possible that Tony was the one who needed help, upon waking from the nightmares. His face turned sullen and he wouldn’t comment. I couldn’t tell if he was ready to give up on blaming somebody else for the shouting in the night. But he didn’t disagree with me, so I pursued the idea that ‘the man next door’ was shouting the things that he himself could not express, begging for help on his behalf.

He dropped his face in his hands, muffling his voice. ‘No … I don’t want to … I can’t be so weak.’ I understood his need not to be vulnerable, I said gently, but on the other hand, as I reminded him, he had asked to see a therapist in the first place. ‘That’s a request for help, isn’t it?’ He grunted, not denying it. I told him I was mentioning this because I thought it could be a reminder that there was a part of his mind that was ready to be vulnerable, that actually wanted to be. At that, he raised his head, and I held eye contact, knowing we’d come to an important turning point. ‘Tony, I think you’re brave enough to look at something really difficult.’ His voice broke, but he didn’t look away. ‘I’m not brave.’ I looked into his eyes. ‘You don’t think so? Well, I experience you as brave. It takes courage to think about past violence, to take your mind seriously and talk about things that are upsetting with me. It’s only in your nightmares that you’re afraid. Here you’ve shown real courage.’

This registered with him, perhaps not immediately but over the weeks that followed, and he stopped complaining about the man shouting in the room next door. Gradually, after many more months of talking about his vulnerability and pain, his nightmares tapered off, and he stopped disrupting the ward at night. The nursing staff were pleased with his progress, as was I. Other members of the clinical team reported that Tony’s symptoms of depression had diminished too. I hadn’t known where therapy might lead when we’d embarked on this journey together, some eighteen months earlier, so I was pleased that his symptoms had improved. The team felt he was ready to return to prison and serve his sentence, and I agreed. Tony was accepting of this, and we began to prepare for an end to our work.

I recalled how I had once doubted whether there was any point in working with Tony, and how some of my colleagues had too. I certainly hadn’t imagined what progress or an ending would look like. This early experience taught me that no matter what their history, if people are able to be curious about their minds, there’s a chance that we can make meaning out of disorder. Tony had also learned to deal with painful thoughts and feelings, even when this was challenging, which would help him cope better with others in the future. I felt as satisfied as any doctor does when they offer a patient treatment and things shift for the better. I’d also discovered something about how I could deal with this kind of long-term therapy work, especially when I made mistakes, as with my early clumsiness in using the word ‘abuse’ about Tony’s father. It was possible to recover the situation and move on from ‘upsets’ – a lesson that would prove invaluable in the years ahead.

*

One of our last meetings began on a fine June day, when the angle of the sun prompted me to pull the shade across the window, plunging the room into a half-gloom. I could not have imagined the turn our discussion would take. Tony arrived promptly, even a minute or two early. There was a little silence as we settled in, but by now he was comfortable enough to start speaking whenever he felt ready. Abruptly, he commented that it was Father’s Day tomorrow. I knew his father had died some years earlier, and I couldn’t think why that might be important. ‘My dad would have been seventy-two by now. That’s no age at all. Dropped dead one day, just like that, no warning.’ He shook his head. ‘No warning at all.’ Tony had told me some time ago about how his father had appeared to be in good health on retirement, only to have a sudden heart attack. It had been a shock to everyone, and the news had come to him belatedly because he’d virtually lost contact with his family. He’d only heard about it weeks after the event. ‘But a lot of blokes drop dead when they don’t have any work to go to any more, right?’ Tony commented without emotion. I hoped he was not connecting this to the end of our work together.

I asked him what the term ‘Father’s Day’ brought up for him; was there something different about it this year? He shook his head, and I had a sense he felt frustrated, as if he wished he didn’t feel anything. ‘It’s just … there was no goodbye. Missed the funeral and everything,’ he said. He looked tearful as he said it, and I told him I thought that must have been very hard. He nodded, and we sat there together for a time, sharing a respectful silence, as if we were at a funeral together. Eventually I asked, ‘When did he die?’ He thought about that, uncertain. ‘Must have been … early August or so. Just before that ginger lad.’ I wasn’t sure who he meant. He hadn’t described any of his victims to me in this way. ‘Let me work it out …’ he was saying, eyes to the ceiling, trying to recall the timing. ‘So I guess it must have been … 1988, and the ginger lad …’

As he did the calculation, I think we both realised at the same time that he was talking about another murder, someone who came before the lovely blue-eyed boy that he had previously identified as ‘the first’. I suppose I ought to have been startled or alarmed, but I remember feeling quite detached and calm. ‘Is it possible, Tony, that there was a fourth death? That before the young man with the blue eyes, there was another man, this ginger lad, who died?’ I chose my words with care, acutely aware that this conversation might be legally important. I could not use the leading word ‘murder’ because that would be for the jury to decide, if it ever came to court. Tony’s defence lawyers could argue that I had influenced their client, coerced him into some false confession.

I felt awed by what was happening, by the way the mind’s erratically placed walls and doors can suddenly hide or reveal unbearable acts and feelings. Opening this particular door would have been impossible if Tony had not been able to speak about all that had gone before, I realised. Despite the horror of what he was saying, I felt honoured to be his witness at this moment. Tony shook his head back and forth, his distress rising. ‘I don’t know, I don’t know … I thought I told them about him, but now I think I didn’t. Oh God …’ He had confessed to

the other three murders soon after his arrest, so why not this one too? I asked if it was because he didn’t know for certain if this ‘ginger lad’ was dead when he left him, which was all I could think of to explain it. ‘No. He was dead all right. I’d just forgotten it,’ he said, his eyes meeting mine. ‘I didn’t even know I wanted to talk about this today,’ he added. ‘But there it is.’ We considered if it was possible that he had somehow lost this memory, or whether it had been eclipsed by his father’s death and his grief.

Our time was nearly up, and I had to let him know what he probably knew already: he had said something important that I would have to share with others. Together we needed to think about what came next. ‘But tell me, how did I forget it all this time?’ he asked, seeming genuinely anguished. ‘How do I explain why I didn’t talk about it before?’ It was an excellent question, and I thought carefully about how to answer. I suggested that sometimes people have to be ready to remember things, to face what they would prefer not to see. Something else occurred to me just then. ‘Perhaps this memory was part of the nightmare too? Something terrible, like the Medusa head, that you dared not look at?’ Tony nodded in agreement. ‘And maybe it’s also coming to mind now because I’m going back to prison. Like I needed to have my mind clear first.’ I agreed that was possible. We went over what I’d say to Jamie and the team, and what would probably happen next, including informing the police. When I said he’d also need to speak with a lawyer, he asked, ‘Can’t I just talk about it with you?’

I gazed at him, this man who so wanted to talk and who felt things so deeply. I thought about how removed he was from the image I’d once had of the ruthless and unfeeling serial killer, and how much working with him had taught me about the delicate management of my feelings, something that was essential in my work. I could feel great compassion and respect for his honesty, as I did in that moment, and still hold in mind the terrible trail of destruction that his mind had created and the tragedy of each of the deaths he had caused. ‘Of course,’ I told him. ‘Let’s talk.’

The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know