- Home

- Gwen Adshead

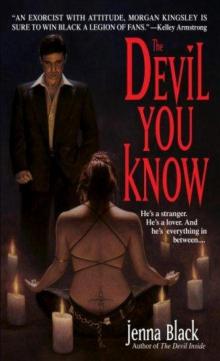

The Devil You Know Page 16

The Devil You Know Read online

Page 16

I had to think about whether her initial meeting with me had stirred up something in Charlie’s mind that had brought on this episode. She had been settled enough when I left her that day, but I knew the emotional significance of any human communication can take time to make itself felt. This is true for all of us, but it may be intensified in the minds of people like Charlie who have spent long periods negating or avoiding their emotions. The mind has so many layers of function it is impossible to know when a certain comment might go off like a depth charge; maybe some paranoia was ignited by my passing comment on her books, or she might have been disturbed by the fact that I had talked about her offence without sufficient preparation. I considered also whether having to wait for gratification (going to the library) had contributed to her violence. I rang her offender manager to ask for more information about her last failed parole and discovered it was an almost exact replica of the current situation; apparently the recall to prison had been precipitated by a row with a member of staff in the halfway house where she was living who had stopped her from going out without the appropriate written permission. It sounded like there was a pattern there.

After her tantrum, I heard that Charlie had not been moved to a new cell, as was standard practice. She had begged to stay where she was, and because she had done no great damage, this was agreed. She was disciplined with a warning, however, and because of her suicide threats, she had to go on the ACCT book – shorthand for a protocol of assessment, care, custody and treatment. This meant her carrying a bright-orange file with her notes at all times, visible as a sign to staff and other prisoners that she had tried or threatened to kill herself. I am sure this was a good idea on one level, as part of the ‘belt and braces’ approach designed by the prison bureaucracy to keep people safe, but I felt certain Charlie must have hated it. Not only could ‘being on the book’ mean taunts and bullying, but that orange beacon singled her out as different, and it was clear to me that Charlie wanted nothing more than to fade into the background, remaining grey and anonymous.

I was right. She was infuriated by the ACCT file, leaving it behind in the dining room and other places around the prison ‘by accident’ more than once, and repeatedly asking to be ‘taken off the book’. She argued that she had never been suicidal in the past and had only talked of wanting to kill herself in the heat of the moment.

Prisons and mental health services always take the tragedy of suicide seriously and cannot ignore suicidal threats, as I’ve described in the case of Marcus. With Charlie, the staff were especially sensitive because only a month earlier, an inmate in a nearby prison who had made a similar threat but not been put on the book had hanged themselves, generating a storm of hostile media coverage. Suicide has been designated as a ‘never event’ in some mental health services, meaning it must never happen, a diktat implying that professionals will be held to account if a patient or prisoner does end their own life. This is unrealistic. Although caregivers may be rightly criticised for errors, some failures of care are systemic, not individual; for example, a doctor may not have the right equipment or training to manage a situation. The self-directed cruelty and despair that drive suicide are as risky as a blood clot or a dying heart muscle; when they are too advanced, there is no hope of medical professionals averting death. It is understood that cardiac surgeons may not be able to preserve life in all cases of heart surgery; by the same token, not all persons intent on suicide can have their lives saved by psychiatrists.

This is yet another example of the fundamentally different perceptions held in our society about mental and physical health services. It is ironic that the only way to maintain a mental health service (both in the community and in prisons) that did not have to bear this risk would be if we stopped offering help to depressed and at-risk people. Some NHS trusts have decided to do just that, to avoid dealing with the difficult legal and social outcomes of having a suicide on their books. This means that when someone is most in need of treatment or a listening ear, they may not be able to access it. The result is achingly predictable.

*

A few weeks later, Charlie and I would have our first proper session, in a small office on the wing normally used by ‘the Listeners’ – prisoner volunteers who operate like the volunteer group the Samaritans to offer support to peers in distress. It was not an especially hospitable or pleasant space, dingy and cramped, with no window. A small glass panel in the door let in a little light and allowed others to look in as they passed by. The room was an odd shape, a sort of thin pentagon, so it was difficult to sit as I would have liked, with a wide space between the facing chairs. As in her cell, we sat opposite each other at awkwardly close quarters. Charlie shoved the hated orange file on the floor under her chair as soon as she sat down, which seemed to me a revealing gesture of how much she didn’t want to talk about her vulnerability. I made a mental note not to let her forget to retrieve it when she left.

Charlie was wearing an ill-fitting tracksuit this time, the swoosh trademark on the left leg a cruel irony for a woman who hadn’t swooshed anywhere in years, her body grown heavy and slack from institutional food and little movement. There was almost no vestige of the skinny girl who was in the photograph I’d seen when I accessed more information about her after our first encounter. Something in that picture – her wide eyes and raised chin signalling a mix of defiance and vulnerability – brought to mind the mugshot of Myra Hindley, an infamous criminal from 1960s Britain who was involved in a grisly series of child murders. A striking image of the sullen teenaged Hindley, with a mop of bleached blonde hair and heavy eye make-up, staring diffidently into the camera, was featured widely in the media coverage at the time of her arrest. I never met her, but I had seen later pictures of her as an older woman in prison. Much like Charlie, by that time she seemed nondescript, unremarkable in every way, but her public identity was bound to the teenage mugshot, fixed in amber.

I quickly understood that Charlie was not in a good mood. She seemed almost unaware of my presence as she launched into a bitter tirade about the orange file, which was ‘fucking ridiculous’. Then she rattled on, wanting to tell me all about the officer she had fought with, her manner and her diction suggesting I might experience this just as she had. ‘Stopping me from reading. Genius idea, yeah? Such a shit, isn’t he, has to control everyone, make himself feel like the Big Man – fuck him, right?’

I kept my face neutral, which is how I felt. Despite some stereo-typical media portrayals and the reality that custodial institutions can attract people who like to bully others, in my experience most prison officers are humane folk who want to do a good job and feel frustrated when they can’t. As when any small group controls a larger one, prison can be a frightening environment for them at times, and their work is hard. It has been made even more difficult by recent staffing cuts within the service, which are estimated at 30 per cent over the last decade, despite the rising prison population. In the last five years alone, assaults on staff in prisons have tripled.2 Most prisons are built in blocks with wings that are then divided into spurs, each housing as many as twenty-five prisoners, usually with just one officer per spur. They have to deal with the mentally ill, the mean, the mendacious, the terrified, the distressed and the self-destructive – sometimes all in one person. This takes a certain amount of tenacity and faith in humankind, I think. I was moved when an officer I met recently commented that it was his view that ‘inside every violent prisoner there’s a good man dying to get out’.

I’ve had to work closely alongside a lot of prison officers, in both female and male prisons, over the years and have found them to be the usual mix of good people and idiots found in any institutional hierarchy, or any walk of life for that matter. Often they are just folk who needed to find work locally, many of them young and lacking in training. Prisoners have described to me their various relationships with officers, ranging from a toxic parent–child dynamic to mutual respect and co-operation. Retention of staff is a problem, with one rec

ent survey reporting that a third of prison officers have less than two years’ experience. I put it to Charlie whether the officer she had tangled with might have seen himself as following prison rules – was that a possibility? This was an effort on my part to see if she could mentalise, if she had that capacity to recognise what might be going on in another person’s mind, as well as her own, or to ‘think about thinking’. Most of us take this ability for granted, but some people find it difficult, giving rise to problematic behaviour.

I expected my comments about the officer might provoke an aggressive response, but instead Charlie surprised me. ‘I know,’ she sighed, and relaxed back in her chair. This was heartening; something about my standing up for another person’s perspective had contained her anger, and there was a noticeable lessening of tension in the room. ‘I lost it with him. Don’t know what got into me,’ Charlie was saying. A familiar phrase, and whenever I hear it from anyone, I think the same thing: whatever it is hasn’t just got in; it was probably lodged there already. But we would go further into this in the course of our work together, I hoped.

Her complaints carried on for most of the session, moving from the ‘bastard’ officer to the library’s ‘crap selection’ of books, with me nodding all the while. Only near the end did I comment that so far it felt as if we’d been talking about things that were external to her, rather than what was going on in her head, in her internal world. She was taken aback and had to think about that for a minute, but then she agreed, telling me that she knew she had to figure out how to manage her angry thoughts. ‘What does anger feel like to you?’ I asked. Without missing a beat, she said, ‘Hot – it feels like dragon’s breath when it comes.’ It was such an evocative turn of phrase. I knew that would go in my notes and I’d give careful thought to it later. Who were her dragons? Were they within or without?

The following week, Charlie arrived on time for our appointment, but she had retreated into herself again and presented as depressed and withdrawn, her gaze on her slippered feet. There was a long silence after she sat down, which I broke eventually by guessing that she wasn’t talking to me this time because she felt uncomfortable. Was that it? She shot me a look. ‘This is stupid. Shrinks never do any good.’ I thought she was testing me; no one uses the term ‘shrinks’ as a compliment, and I don’t know any psychiatrist who doesn’t feel dismissed or belittled by it. I’ve no idea where it derives from, but the association with shrunken human heads used as trophies is not a comfortable one. Charlie’s choice of the word made me consider whether she saw psychiatrists as the enemy. I stored that thought away with the dragon; it really wasn’t my job to defend my profession, and anyway, I wanted to acknowledge her experience that the previous psychiatrists she had seen had ‘done her no good’. I tried to do this by asking if her comment about shrinks was a sign of hopelessness. Her eyes narrowed. ‘Why should I have any fucking hope? Is that what you expect from me?’ I was interested that she was guessing at what I was thinking. ‘I know what you want, you people … it’s for me to have remorse, right? Sorry, but I don’t. I was much younger back then … when it happened. I’m not the same person now, and I don’t feel sad about it. Sorry. Sod off. I’m not going to fake it.’

This was complex. She was bright enough and had been in the system long enough to know that forensic and prison professionals do take an expression of remorse as a sign of a diminished risk of future offending, and ‘prisoner expresses remorse’ will appear on a checklist for parole evaluations, as an indicator of lower risk. It is a nice idea, if it were true. The problem is, there’s little evidence for it, or rather, it appears from the available data that a feeling of remorse is one of the least important elements in successful risk reduction. This was initially surprising to me, but over time I’ve witnessed how much more relevant positive factors are, such as a pro-social attitude, investment in getting care and help, and a genuine understanding that a change of mind is necessary in order to have a change of life in the future. In my experience, regret is easier for offenders to access. It is less personal and emotionally punchy than remorse. It may also be more functional because it can act as a motivator for new choices; it is also a verb that implies change, and taking action to change is essential to a new way of thinking and behaving.

I had never mentioned the word ‘remorse’ to her and found it interesting that she was attributing thoughts to me that were her own. It was possible that at some level she wanted to feel remorse because she knew she ought to. It could also be that her anger was driven by an anxiety that I was seeing her only as the Charlie of the past, the teenage kid in a faded mugshot, and not as the mature woman that she was now. Her idea that remorse might have an expiry date was also fascinating and I wanted to return to it later, but for now, I validated her line of thinking. ‘Okay, that’s clear to me. Remorse is not real for you, and you want to be honest about that. What about regret? Do you have regrets?’

‘Of course!’ She was still angry, but not at me, I thought. ‘I don’t know how it all happened.’ And suddenly, she was taking me to the night of the murder. I was with her in the park as night fell, and with her as she recalled running after the others, racing across the grass in bare feet, stoned and hungry, following their lead. She described in vivid language how she was ‘swept up’ in the gang’s unanimous surge of anger and disgust at the old tramp, joining in as everyone went after him. Someone was grabbing his booze, pulling his sleeping bag out of his grip as he begged them to stop – and then she and an older girl, someone she looked up to, pushed him to the ground. She heard an awful sound as his head hit the gravel and saw some blood leaking out of his ear, but she told me it all felt disconnected from her, ‘like I was looking at a photograph or something’. She gazed past me as she relived this, her eyes unfocused, her face impassive. ‘He just lay there, you know … sort of twitching a bit, and then … he was dead. And I was part of it, and I do regret that. But you can’t go back. You can never go back. Never ever, not ever.’ Her repetition reminded me of Lear cradling poor Cordelia in his arms, his agonised lament of ‘never, never, never, never, never …’ defining heartbreak with perfect simplicity. He was facing the same devastating truth that Charlie was articulating now: death cannot be undone.

I felt that we were beginning to explore the chaos of Charlie’s inner world. I observed that she oscillated between a view that she had to use violence to influence events and emotions, and feelings of compliant helplessness and despair. This vacillation is a familiar feature in patients I’ve seen who have been exposed to high levels of childhood trauma and adversity, and I’ve come to see those extremes of violence and passivity as two different and useful personas – a word derived from the ancient Greek for ‘stage mask’. The mask metaphor is such a useful one for thinking about how the mind works in social situations, as we take on or set aside different qualities, depending on certain emotional cues. It is no surprise that Shakespeare memorably describes life as a stage in his plays, with all the ‘strutting and fretting’ men and women ‘merely players’.

It occurred to me that the persona of Violent Charlie reflected a Just World hypothesis, an idea devised in the 1960s by American psychologist Melvin Lerner. From his extensive research, he found that humans were broadly disposed to think that beneficiaries merit their blessings and victims their suffering; or, put simply, good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people. This ‘just deserts’ way of thinking is still prevalent today. It may even explain why some victims become perpetrators, a recurrent theme in forensic work, as we’ve seen. Charlie and others like her internalise their experiences of abuse and trauma to create a belief that if they are excluded from a world where good things happen, then the associated senses of loss, rejection and envy become toxic drivers for more ‘badness’. They may also feel a need to exert ever more control over others to protect themselves from the badness of their lives and the punishment that the ‘good people’ will hand down.

Her other perso

na, Passive Charlie, believed that everyone around her had greater power and agency than she did. In this state of mind, she didn’t have to take responsibility for anything. ‘I still don’t know how it happened,’ she had said, just before giving me a precise account of how the murder of Eddie had unfolded. If, as she’d put it, she was just ‘swept along’ and nothing she did was her choice, she could avoid difficult feelings. It was the gang, it was an older girl, it wasn’t real to her, it was ‘like a photograph’. I understood how that narrative had helped her to keep shame at bay, which may have been the only way she could bear to go on living. I began to think the suicide threat she had made to the prison officer had not been idle, but so far she had suppressed those feelings by telling herself a story that kept her safe.

We continued to meet together for some months, and she was increasingly able to talk about her feelings and the past. Her moods would still swing from week to week, but I became better able to assess which mask she was wearing and discuss it with her as soon as she entered the meeting room. We talked about some other stories from her life, and I was interested too in any fictional stories she had read and liked. In one session, I reminded her of our first encounter in her cell, when I’d asked her about the Vikram Seth novel. Did she know why she’d picked that one to read? But she was Passive Charlie that day, and she shrugged, unwilling even to take responsibility for her choice of reading material. It was then that I suggested she might want to look at William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. The novel had an obvious resonance which could be upsetting for her, I knew, as it described a band of boys who commit a murder together, but I had a feeling it might be relevant to our work.

The Devil You Know

The Devil You Know